A few photos from about 20 years ago. They were taken in Cumbria, Derbyshire and Dumfries & Galloway.

Prehistoric

Some moorland stones

I took a trip over to Glaisdale to visit one on my favourite North York Moors standing stones. This rarely visited, tall, beautiful stone is one of a pair of upright stones located on Glaisdale Swang

Swang – a boggy stretch of land.

When I arrive at the stone I’m confronted by an anxious pheasant hen who starts running in circles around me, a tactic designed to distract me while her brood of chicks scatter for the shelter of the nearby heather.

I can see another stone on the moor edge in the distance, I know that this will probably be a guide stone but probably isn’t good enough, I head for the higher ground. The ground is marshy, so I zig zag my way up the narrowing valley following the lush green carpet of bilberry which tends to grow on the better drained ground. Curlews and lapwings rise in alarm and noisily track my progress as I move from one birds territory to another. Towards the top of the swang, a large hare breaks cover.

As I move onto the high moor guide stones mark the track. Many of these stones date to the 18th century, others may possibly be far older. On October 2nd, 1711, the Justices sitting at Northallerton ordered that guide posts should be erected throughout the North Riding.

A solitary pine tree on the moor top, its branches indicate the direction of the prevailing winds.

Walking across across the high moor towards Glaisdale I encounter a couple of low standing stones one of which is close to a low mound. These stones are not on the track and are too small to be guide stones. Another group of large stones look as through they were once standing but it is difficult to say much more about them.

This guide stone was carved and erected by Thomas Harwood about 1735. Harwood erected four other similar stones on Glaisdale Rigg. The stone appears to be housed in an old cross base. It is possible to make out the inscriptions on the north and east faces, they read Gisbrogh Road and Whitby Road. The other two faces are illegible, Stanhope White writes that the south face reads Glaisdale Road TH.

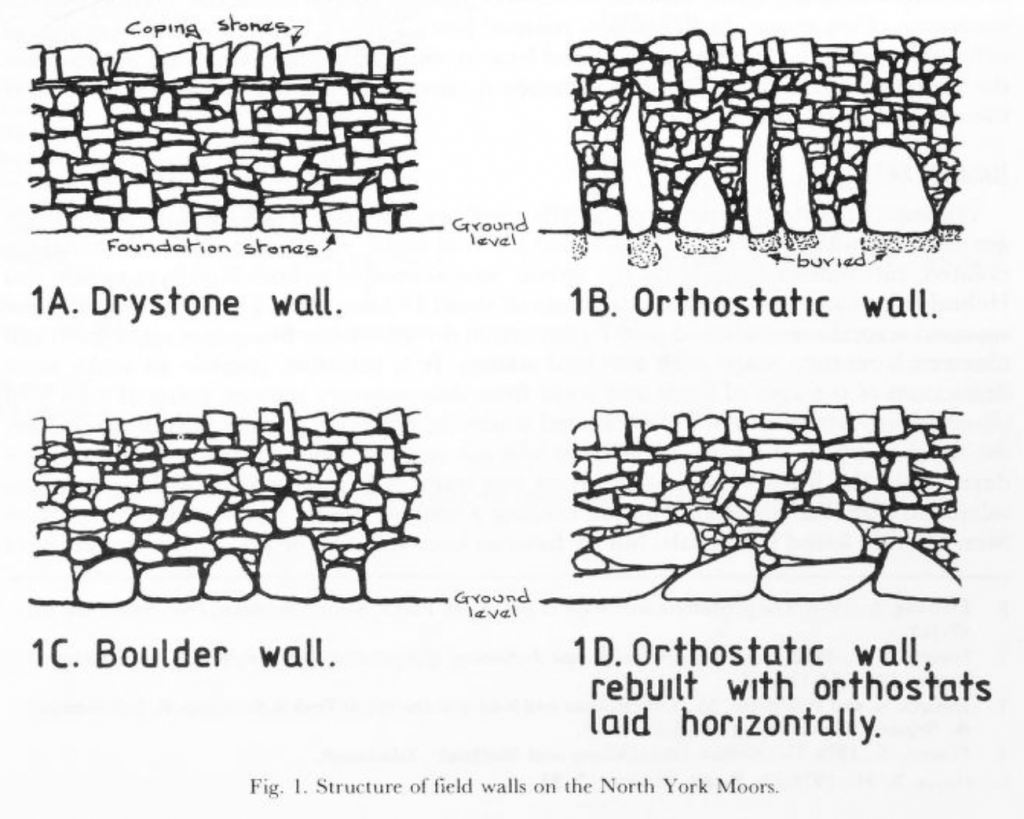

Walking over to the edge of Glaisdale I find this beautiful orthostatic wall, a real joy. About a century ago many of the original field walls across the moor and dales were rebuilt by professional wallers, this wall may be a survivor of an earlier age.

In his book, Some Reminiscences & Folk Lore of Danby Parish & District, Joseph Ford writes of Stone-Rearing Days. These were occasions when a farmers neighbours gathered together to build walls around newly-enclosed fields. Ford thinks that this tradition may stretch as far back in time to the original settlers of the moorland dales.

Etymology

Glaisdale – YN [Glasedale 12 Guisb. Glasedal 1223, Glasdale 1228 FF] ‘The valley of R Glas’

OW gleis, Welsh glais ‘stream’

Glas is a British river-name derived from the Welsh glas ‘blue, green, grey’

Sources

Yorkshire Wit, Character, Folklore & Customs. R Blakeborough. W Rapp & Sons Ltd. 1911

The North York Moors. An Introduction by Stanhope White. The Dalesman Publishing Co. 1979

Some Reminiscences & Folk Lore of Danby Parish & District. Joseph Ford. M.T.D. Rigg Publications. 1990

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Placenames. E Ekwall. 1974

Orthostatic Field Walls on the North York Moors. D.A. Spratt. Yorkshire Archaeological Journal No. 60 1988

Wade Stones 2002

I found a box of some of my old photos.

I used to take my kids out on stone finding expeditions. My daughter once told me that she would call Childline if I took her to see another stone circle.

A day out with Mr Chappell

Dialstone House – Cold Kirby Moor – Thirlby Bank – Whitestone Cliff – Fairies Parlour – Hambleton Down – Boltby Scar Hillfort – Cleveland Road

You can read Graeme’s account of The Fairies Parlour here

Howe Hill, Felixkirk

Howe Hill is a prominent mound in the centre of the village. It was previously thought to be a Norman earthwork or Motte but is actually a prehistoric burial mound dating from the Late Neolithic period to the Late Bronze Age. The site is still marked on the modern maps as a Motte.

The barrow has a beautiful tree growing on it and sits upon a natural knoll that has been bisected by the main road into the village. The primary views from the barrow are to the west across the Vale of Mowbray to the distant Pennines.

There is a Norman connection with the village, the local church was rebuilt in the mid-nineteenth century contains a number of Romanesque carved stones including this lovely capital depicting foliate heads.

The Smell of Water Part 3: Danby Rigg

Horn Ridge Dyke

In common with most people I feel as though many aspects of my life have been on hold for the past 12 months. My list of places to visit gets longer and longer. Now that lockdown is easing I seem to have a mental log-jam of what to do and what to see.

I have been planning on visiting the Cross Dyke of Horn Ridge for quite some time as it is one of the few local dykes that I haven’t visited. Once again, it was a chance online conversation with a friend that spurred me into action.

The sun was shining, the forecast was giving out wintery showers, this was perfect for me, half decent weather and less chance of meeting anyone on the moor-top.

I drove down to Farndale and walked up the keepers track that runs up the side of Monket House Crags. The track is not too steep and takes you through an area covered in spoil heaps from the 19th century jet workings. When I started walking the sun was shining, within a few minutes a wintery squall blew in from the north leaving a dusting of snow on the hillside. The squall was intense but short-lived, this became the pattern for the rest of the day.

I followed the track south along the gentle rise of Horn Ridge. From the high point the land begins to gently slope down to the south, the eye is drawn along the valley of the River Dove to the dale end with the moorland above Hutton Le Hole and the Vale of Pickering in the far distance.

As you walk down towards the very obvious earthwork you become very aware that you are on a narrowing promontory of moorland , the fertile dale on either side, hemmed in by the dark domineering presence of Rudland Rigg to the West and Blakey Ridge to the East. As you near the Dyke you can see through the central gap to a fairly level area with the barrow beyond, the effect is quite striking.

The Dyke itself runs the full width of the upland, terminating where the land drops off at either end. Its total length is approximately 300m.

Approaching it from the north it appears to be quite an impressive earthwork fronted by a deep ditch that has been dug along its whole length. When viewed from the south it appears less imposing.

A section of the Dyke was excavated by Raymond H. Hayes. He was unable to find any evidence that might give a date to the earthwork. He observed that with the ditch ‘its builders did not cut the rock as in Iron Age or Roman ditches.’

There are a couple of stone settings within the dyke on the south side but these look relatively recent, a modern shelter or grouse butt and a trap built by keepers to catch small mammals. These moors are not a friendly place for any creature that vaguely threatens the grouse population. Last year 5 dead Buzzards were discovered hidden beneath a rock just 3km north of the Dyke.

Walking south towards the barrow, a squall blows through and the views are lost.

The barrow is a sad sight. It’s quite large, approx 10-15m diameter. It’s hard to fully gauge the dimensions due to it’s in a terrible state of repair of the structure. The scheduling entry for the monument mentions ‘a central excavation hollow around 4m by 2m, with a second 1m diameter pit in its west side.’ The keepers have also recently built a trap into one of the holes in the mound.

I took wander over to the western edge of the ridge. There are reports of cairns and hut circles in this area. I was just starting to spot them when it started to snow quite heavily. My mind turned to driving home and having to tackle the steep bank from the dale bottom up to Blakey Ridge. Under normal circumstances I wouldn’t mind being trapped in Farndale but with the current conditions i.e. the Feversham Arms being closed, I decided that the western edge of Horn Ridge was one for another day and turned for home.

Sources

A History of Helmsley Rievaulx and District. 1963. Editor – J McDonnell

The brides of place: cross ridge boundaries reviewed. – Blaise Vyner. In Moorland Monuments CBA Research Report 101. 1995

The Tank Road

Death and Remembrance

We needed a walk but didn’t want to travel far from home…Thunderbush Moor along the Whiteley Beck valley and then up to North Ings and the wonderful Bride Stones.

The trees planted in the valley are growing well. In a few years this will be a lovely broad leaf woodland

Someone has decorated a tree in memory of a lost friend. Amongst other things they have left a beautiful photograph, a joyful scene.

A painting has been added to the memorial to the two pals who lost their lives during the First World War

The heather is low on the edges of the prehistoric cairnfield, a trio of burial cairns poke through the peat beside the path.

We follow the Bride Stones from the valley head onto Skelderskew Moor .

I wrote a post on the history of this short valley here https://teessidepsychogeography.wordpress.com/2014/06/08/stones-shakespeare-and-men-of-the-moors/

The Cammon Stone

The Cammon Stone from the Celtic ‘cam’ meaning bank stone. On its leaning side is a Hebrew inscription HALLELUJAH which was one the source of much controversy as it was thought to be Phoenician but can be compared to the Hebrew lettering on the Bransdale Mill inscription. It is most likely the work of Rev. W. Strickland a 19th century vicar of Ingleby.

Source – Old Roads & Pannierways in North Yorkshire. Raymond H. Hayes. NYMNP 1988