Stone Circle

Midmar Kirk

‘Surrounded on all sides by crosses, the Recumbent stone circle & flankers of this circle look for all the world like the gigantic horned god rising out of the living earth.‘

The Modern Antiquarian. Julian Cope. 1998

South Ythsie

Etymology – Ythsie (for Suidhe Chuith). Place near a fold. Suidhe, site, place; chuith, gen. asp. of cuith, fold. By transposition the name had become Chuith Suidhe. Ch had become silent and had been lost with u. Suidhe had lost dh, which is often silent. There remained Ith Suie, which is now Ythsie. Source

Easter Aquhorthies

Standing on a gentle hillside and unfortunately incarcerated in a modern drystone wall, this is a beautiful site to visit. Its prehistoric builders had pleasing polychromatic tastes.

A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland & Brittany. Aubrey Burl. 1995

Etymology – The name derives from Gaelic and has been interpreted as ‘field of prayer’ (from ‘auch’ or ‘achd’ meaning ‘field’, and ‘ortha’ meaning ‘prayer’) or ‘field of pillar stone’ (‘achadh choirthe’).

Megaliths, golf & a dead van

My van died climbing the Garlic Bank on the Hill of Tarvit just south of Cupar, Fife. The AA man’s verdict, one of the vans injectors was broken and needed to be replaced immediately. When asked where I was going, I told him I was heading for the ladies golf course at Lundin Links to have a look at some big old stones. So van in tow, we headed south to Lundin Links.

Being towed by a large yellow van with a flashing beacon ensured that our arrival at the Lundin Links Ladies Golf Club members-only car park, was noticed. There were a couple of people around so I went to ask permission to park-up until help arrived.

Everyone was really nice and directed me towards a man who was walking across the course with a television set under his arm. I told him that I’d come to visit the stones and explained my predicament. I followed him into his office, which was located on the edge of the green. He told me that he’d brought the tv to work so he could watch the horse racing. He also told me that it was my lucky day because he knew all about the stones.

He then went on to tell me about the stones and how there was once four stones that formed a circle but the former location of the missing stone is now unknown. He also told me about some of the strange encounters that he’s had with visitors including barefoot Americans ‘re-grounding’ themselves around the stones, naked dancers and the solstice gatherings of druids on the golf course. And yes it was fine to park in the car park, he even told me that I could use the club’s toilet and where the nearest cafe was.

I thanked my new friend, wished him luck with his horses and took a wander around the edge of the course towards the distant stones. The man had warned me to take care out on the course as there were two Doctors currently playing who were very poor golfers. I stopped and had a chat with one of the Doctors who admitted that he found golf a very difficult game to master.

The first glimpse of the stones was jaw-dropping. Their sheer size and sculptural qualities are something that can’t really be conveyed through images, you have to experience them in the landscape to appreciate how truly wonderful they are. Julian Cope describes the three massive pillars as The Stenness of southern Scotland, I can’t argue with that.

The day before my visit I’d been staying at a place in Aberdeenshire that was in the shadow of Mither Tap. Whilst there I’d visited a few megalithic sites that all had a view of the distinctly-shaped hill. I couldn’t help but draw a comparison to the relationship between the Lundin Links stones and nearby Largo Law.

The mechanic arrived and replaced the injector on my van, it was time to leave. It was a four hour drive home, an hour of which was spent in a very slow traffic crawl around the Edinburgh bypass. The breakdown, the traffic, I didn’t care, it was all worth it to visit these wonderful stones.

Doom Tuba – Fellfoot Sounds

When I saw the flyer for the Fellfoot Sounds event I jumped at it, I knew my friend Martyn would also be keen to attend. Who wouldn’t enjoy the prospect of spending a couple of days in this lovely corner of Cumbria in the company of a group of sound artists and musicians? It turned out, Martyn knew many of the people who were working at the festival.

Martyn and I arrived at the lovely Into the Woods site, ticket sales were limited to 150 so the place had a nice relaxed, family-friendly atmosphere. The campsite is set-up around a large field with a bar, stage, kitchen, clubhouse and various other facilities on site.

We went along to a couple of workshops, Field Recording and Sampling with Jayne Dent and Folk Voices with Jennifer Reid, both of which were excellent.

On the evening the artist’s performances were held in the lovely nearby church of St. Michael and the Angels. The little red sandstone church was the perfect venue. Jorge Boehringer filled the church with the sound of his droning distorted viola, I’m currently listening to this as I write. Jayne Dent followed with a piece built around sound samples and field recordings collected during the earlier workshop. Jayne performs as Me Lost Me, her latest album, RPG is currently getting lots of play in our house. Ore concluded the performance with an improvised piece played and tuba, trombone and a pair of resonant gong speakers which I found mesmerising. You can find their work here, I can now add Doom Tuba to my list of favourite musical genres.

The sound artist performances combined with the setting left me feeling calm, slightly entranced and ready for the wander to the stone circle. The procession was led by the gold foil bedecked Noize Choir. We walked along an ancient holloway dodging deep muddy puddles and the entrances to a large badger sett, it was a joyful chaotic affair.

On arriving at the stones half of the group walked around the circle in a clockwise manner around the stones, the other half went anticlockwise, the air was full of laughter, chanting and children shouting. There were a number of people visiting the stones when we arrived, I’m not sure what they made of our rag-tag group but I’m pretty sure that our arrival will have created a lasting memory of their visit.

Returning to the campsite, a large fire was burning, people were eating and drinking and generally having a good time. Folk artist Jennifer Reid topped off the night with a brilliant performance of chat and songs. Jennifer’s energy, humour and positivity is completely infectious, she’s wonderful.

The following morning, after a great recovery breakfast from the kitchen, we headed over to the stone circle for Paul Frodsham’s walk and talk around the stones. Paul is a professional archaeologist who has worked throughout northern England. He told us that he has had a lifelong interest in the Long Meg circle since first visiting it as a student. He an led an excavation at the circle in 2015.

Paul started at the Long Meg standing stone and talked about his theory that the carvings on standing stone may have been made prior to the stone being transported from the banks of the river Eden to its current location. He then moved onto the stone circle describing the structure of the circle and its alignment to the winter solstice. He also explained how there had been a large enclosure around the area now that is now occupied by the farm buildings. This enclosure predated the circle and is the reason that one edge of the circle is flattened.

Paul also expressed his frustration at how little investigative archaeology, compared to other large British prehistoric monuments, has been done at what is essentially one of the oldest and largest stone circles in our Islands. Paul is trying to redress this issue but to do so requires resources and funding. He is also working with others to set up a Friends of Long Meg group to promote the and hopefully attract resources for further investigations.

All in all I think everyone who attended this little family-friendly festival had a very positive experience. The site was lovely and organisation of the event was first rate. Well done to everyone involved, I look forward to future events.

The Blood and Bones of the Land – Yockenthwaite

Langstrothdale – ‘Long Marsh’

Yockenthwaite – ‘Eogan’s Thwaite’

Wharfe – ‘Winding River’

From the river-name is derived Verbeia, the name of the deity, found in a Roman inscription at Ilkley.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names. Eilert Ekwall

Research on Verbia – Dreamflesh

Wandering in the shadow of the sacred hill

My friend Graeme Chappell and I decided to have a wander around Thompson’s Rigg. We followed the Old Wife’s Way from Horcum, dropping down along Newgate Brow into the valley below.

We crossed the fields to take a look at the standing stones at the foot of Blakey Topping. These stones have been interpreted as a possible ruined stone circle.

After spending some time at the stones we walked onto Thompson’s Rigg. The Rigg is only a mile long, its flanks slope down into the valleys of the Grain Beck to the East and Crosscliff Beck to the west. The moor is surrounded on three sides by higher ground and gently slopes to the south where it narrows to form a valley which eventually leads to Langdale End and Howden Hill, a hill very similar in appearance to Blakey Topping.

About a third of the way along the Rigg the trackways bends, at this point, running diagonally to the trackway, is a cross ridge boundary. The boundary is a banked structure that bisects the full width of the moor and is topped, in parts, with large stones. The official scheduling for the area states that, Although this boundary forms part of the post-medieval field boundary system in the area, it is considered to incorporate elements of an earlier construction which had origins in the prehistoric period, contemporary with the cairnfield. source

In his book Early Man in North East Yorkshire Frank Elgee wrote, A wall of upright stones crosses the Rigg between the farm and the barrows, he also includes the boundary on his map of the area

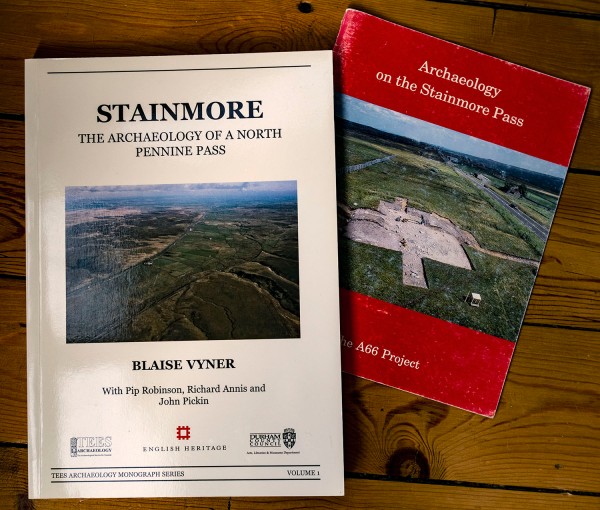

It is curious that despite the earthwork being mentioned in the official scheduling of the area and despite it defining the the northern limit of the cairnfield and barrows and its close resemblance to other moorland cross ridge boundaries, this significant structure does not appear in either Don Spratt’s 1993 or Blaise Vyner’s 1995 inventories of the cross ridge boundaries of the North York Moors.

South of the large boundary earthwork we started to encounter many cairns, most are in deep heather and difficult to define, at least one of this group appears to be a large ruined barrow.

We continued south, traipsing through the deep heather to a grassy area containing a beautiful Platform Cairn. Platform Cairns are rare on the North York Moors, they are defined as, A roughly circular monument featuring a low, more or less level platform of stones surrounded or retained by a low stone kerb. Some may feature a small central open area, thus resembling a ring cairn. Source.

There is a large stone and hollow in the middle of the cairn implying a possible ruined cist, it is evident that this cairn had been excavated in the past. Graeme reminded me that we were only seven miles from Pickering, once home to James Ruddock.

James Ruddock was a nineteenth century commercial barrow digger. Between 1849 and his death in 1859 he opened many of our moorland mounds in search of finds to sell to the gentleman collectors of his time. His main client was the antiquary Thomas Bateman, he also opened barrows for Samuel Anderson of Whitby.

Unfortunately Ruddock did not always keep precise notes regarding the locations of his diggings, many of his finds have ended up in our museums with vague labels such as, from a mound 6 miles north of Pickering.

Moving further south we encountered this lovely, fairly well-defined ring cairn.

On the south eastern flanks of the Rigg is a group of hollow ways, these are not considered to be prehistoric.

At the southern end of the Rigg is this orthostatic wall which contains many large stones, some of which appear to be buried into the ground. If the wall contained unburied stones it would be classed as a boulder wall. The walling is definitely not prehistoric but may contain stones from an earlier feature.

Not far from the walling is this three foot high standing stone, located within an area of low banks and cairns at the southern end of the Rigg.

Blakey Topping and Thompson’s Rigg are well worth a visit, There is a wealth of prehistoric remains to be seen within a relatively small area. The area is owned by the National Trust and is not managed for grouse so has a mixture of habitats, we saw plenty of birds including Skylarks, Snipes and what I think were a large flock of Fieldfares.

If you visit this lovely place, what you’ll undoubtably notice is that wherever you are on the moor, Blakey Topping is the dominant landscape feature. Graeme and I agreed that this beautiful hill probably had a deep significance to the original inhabitants of this area. A sacred hill? perhaps even a sacred landscape?

Resources

Early Man in North East Yorkshire. Frank Elgee. 1930

Orthostatic Field Walls on the North York Moors. D A Spratt. YAJ Vol. 60. 1988

Linear Earthworks of the Tabular Hills, Northeast Yorkshire. D A Spratt. 1989

Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology of North-East Yorkshire edited by D A Spratt. 1993

CBA Research Report 101: Moorland Monuments’ in The Brides Of Place: Cross-Ridge Boundaries Reviewed, B Vyner. 1995

OS Map – The National Library of Scotland

Postscript

To illustrate Graeme’s comments

Rey Cross ii

OE stan ‘stone, stones’ is a very common pl. el. It is used alone as a pl. n. in STAINES, STEANE, STONE, where a Roman milestone or some prominant stone of another kindmay be referred to.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Eilert Ekwall. 1959

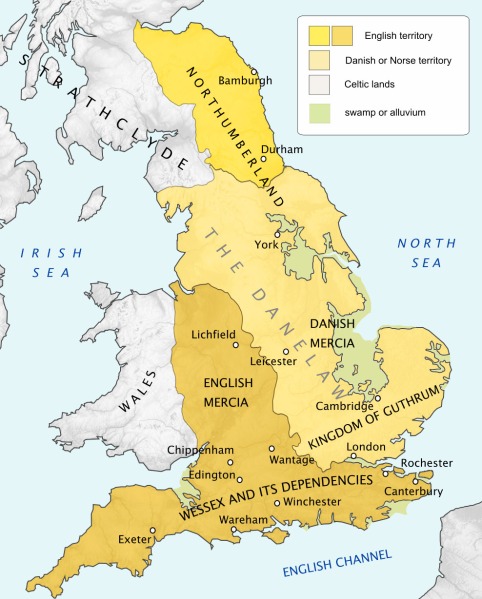

I recently took a trip over the Pennines to Cumbria. On the way home I stopped on Stainmore to have a look at Rey’s Cross. The Cross is located in a lay-by beside the A66. The A66 crosses the Pennines through the Stainmore Gap, a Pennine pass that was created by the flow of ice sheets during past glacial periods.

Historically, This part of Stainmore has always been important. The moor is rich in late Prehistoric remains. It was also the site of a large Roman marching camp, within the ruins of the camp is a wrecked prehistoric stone circle. Legend has it that the stone cross was raised as a memorial to Eric Bloodaxe, the last king of York, who was slain on the moor in 954.

The cross, situated near the highest point of Stainmore, is close to an ancient county boundary, is a weathered shaft set into a substantial stone base and is thought to date to the early anglo saxon period. The name`Rey’ is thought to have been derived from the Old Norse element `hreyrr’ which can be taken to mean a heap of stones forming a boundary.

One of the earliest references to the stone is from The Chronicle of Lanercost where it is call ” Rer Cros in Staynmor ” The chronicler states that it was set up as a boundary marker. The boundary was between the Westmoringas and the Northumbrians, the Glasgow diocesan border, before that it marked the border between the Cumbrians and the Northumbrians.

The antiquarian William Camden tells us ” This stone was set up as a boundary between England and Scotland, when William (the Conqueror) first gave Cumberland to the Scots.” Camden was incorrect, at the time of the Norman conquest much of Cumberland was already under Scot’s rule. The historic county of Cumberland was not established until 1177, however the stone could still have marked the boundary of the territory.

The A99 was widened in the early 1990’s so in 1990 the stone was moved from the south side of the road to its present site on the north side. An archaeological survey and excavation was undertaken as part of a wider archaeological project, sadly no burial was found beneath or around the stone.

What fascinates me about this stone is that it marks a place that has been significant to the people of our islands for thousands of years. The people of the Neolithic period used this as route way between the east and west coasts. Later, the people bronze age erected a stone circle close to the site. Later still, the Romans heavily fortified road to guard the legions marching between Catterick and Penrith and it has remained the primary northern trans-pennine link ever since. A hundred or so metres west of the stone is the modern east/west boundary between Cumbria and Durham and the route was also once the medieval border between Scotland and England. East meets west, north meets south all within sight of the weather-beaten old stone.